Apart from being beautiful, it is HOT and really HUMID in The Bahamas. The locals are used to it, and visitors put up with it just to be in The Bahamas. We certainly put up with it during our visit this past July, and it was so worth it.

I mean, really. So worth it...

To get a break from it, we either plunged in to clearest water we've ever seen...

...took refuge in the shade of some beach-side bar...

...or, found shelter inside with the comfort of nice, cool and dry, conditioned air of our rented beach cottage. As much as we prefer 100% fresh air, we also appreciated the break from the hot and sticky.

This brings me to the whole reason we were even in The Bahamas to begin with. I was hired to design the Air Conditioning, Heating (yes, heating too), and Ventilation (HVAC) systems for a home on a private island near Great Exuma. Below is the view from my temporary "office", which was 1 of 2 RVs that the builder set up for consultants and construction supervisors. Not bad, eh?

The "Bali" House

The design of the HVAC systems for this home was somewhat complicated (which I enjoy very much). Not just because of the weather conditions, but also because the architecture of the house didn't exactly "favor" conventional, or even non-conventional, ducted systems. It wasn't the curves, multiple buildings, or 18'-0" sculptural roofs that made this house particularly challenging. It was the fact that the design of the home was not designed to fully accommodate any type of air conditioning systems, other than, perhaps, a system without duct work. In the case of this home, the owners "do not want to see or hear" any part of the mechanical systems. Not the equipment, and especially not the air. So, a very quiet, low-profile, concealed ducted systems was about the only option. Selecting that system and getting it to fit within the architecture of the home is where I fit in, and in a few weeks (finally) we'll be headed back down to supervise the installation by a Nassau-based HVAC contractor.

Before I talk particulars and geeky stuff, here's a quick photo tour of the exterior of the home, referred to as the "Bali House" for it's Balinese-them architecture and interior design.

THE DESIGN, PART I - Weather Conditions, Great Exuma, Bahamas

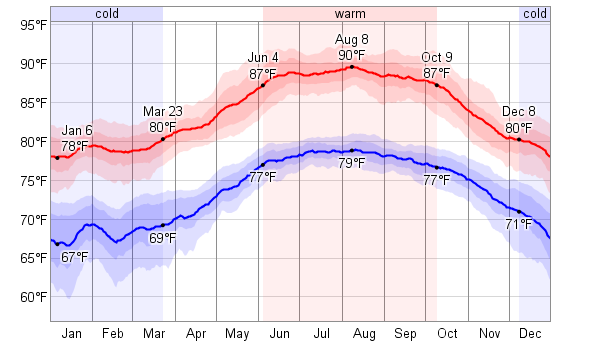

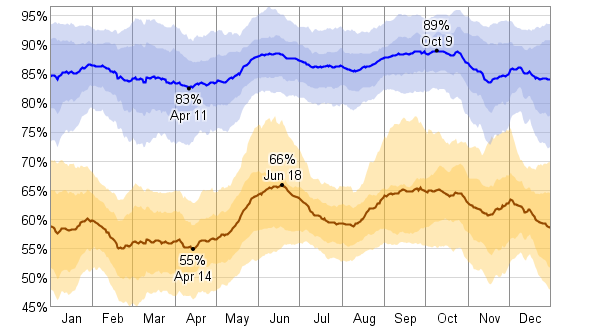

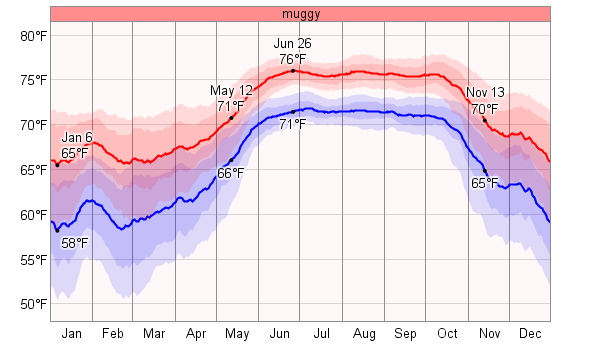

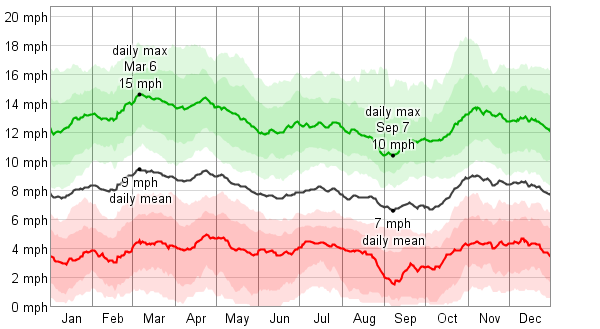

As I mentioned above, no matter where you are in The Bahamas, or what time of year it is, it's typically hot, humid and breezy. When it's not breezy, it feels even hotter. Here is the Average Weather for Georgetown, Great Exuma, The Bahamas, which is just south of the island where this home is. Below are a just a few of the weather factors that are important when designing any home and its mechanical system. I made slight adjustments when design the systems for the "Bali House" based on its precise location design.

The average high temperature, in early August, is around 90 degrees Fahrenheit, and the average low, in early January, stays around 67 degrees Fahrenheit. According to the locals, the lowest temperature they've ever experienced is 60 degrees Fahrenheit.

The average high RH is pretty steady around 86%, and the average low has a slightly bigger swing between 55% and 66%.

The dew point temperature (i.e. when condensation occurs) is relatively close to the actual air temperatures (shown above), which tells us that the specific humidity (the ratio of the water vapor to total air) is fairly high. This is why it feels sticky most of the time.

Finally, a look at average wind speeds gives us an idea of the wind's contribution to air leakage (faster wind = greater pressure on the house = more leakage), which affects the heating and cooling loads, and ultimately the equipment size and type for the home.

Mind the Salt

On the next island over from the "Bali House", the same owner built the "Mexican House". For one reason or another, it has been left vacant and incomplete for approximately 3 years. They've recently taken steps to finish it (our next project with them), which is why you see a fresh coat of paint. In Image 12 and 13, you can see what happened to the steel reinforcement bar that has been exposed to the "Bahama Breeze" while the house sat unfinished.

The salt-laden moisture being pushed around by the ocean breezes has corroded the exposed steel reinforcement bars (re-bar). For this reason, a lot of outdoor mechanical equipment, made of metal, is given a protective coating to extend its useful life. Although it does reduce a system's efficiency and performance, there are some coatings that minimize this loss and do not void the manufacturer's warranty. BlyGold is one of these, and the one we specified for all exposed equipment in the "Bali House".

If we were to install a dedicated fresh air ventilation system in the "Bali House", we would also apply the protective coating to the insides, and use stainless steel ductwork for the intake and supply. The reason for this is that mechanical fresh air systems (e.g. ERV, HRV, in-line fan) use a motor to drive a fan that pulls the outside air in. That air flows through these systems, made mostly of metal, and it would not take long for the insides of these systems to corrode just like this re-bar of the "Mexican House". Replacing corroded equipment is much more costly than this one-time coating.

THE DESIGN, PART II - The opportunities in the Architecture

Here are a couple examples of what I typically see when designing mechanical systems for historic homes, and the owner has requested a ducted systems. The two photos below are from a home on near St. Michaels, MD (eastern shore), where the owner was reluctantly going to use duct-less mini-splits everywhere, until he discovered that there are ducted mini-splits that are smaller, concealed, versatile, and usually have smaller ductwork than normally seen with conventional systems. After a week at this house, we came up with a design that required only one dropped soffit (12" wide x 8" high) for one run of duct. Everything else fit within these small areas, which I asked to be brought in to the building enclosure by installing rigid foam on the outside, and employing other air sealing and moisture management methods.

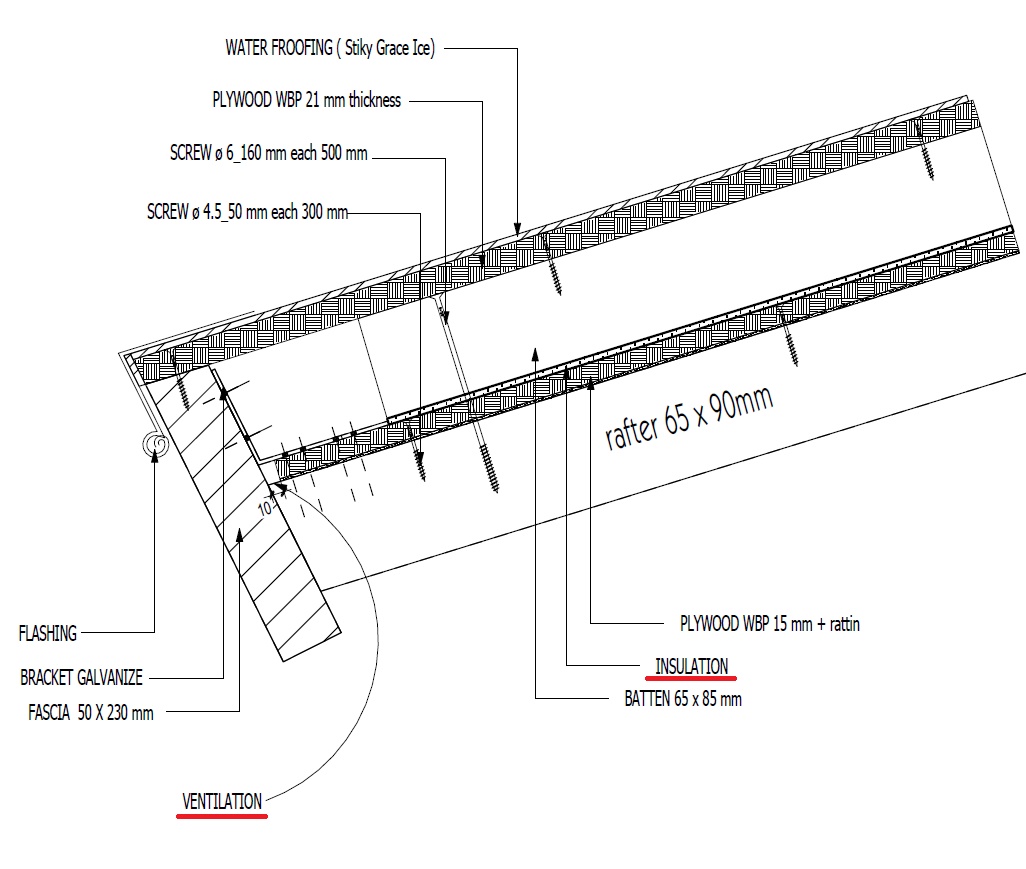

The "Bali House" is mostly an all concrete and block house, with the exception of the Main Living area and Guest House. They are both covered with a sculptural roof feature (made in Bali) that has a continuous ventilated attic (see in Image 19) that is no more than 6" clear. The rest of the house with concrete roofs that are 6" - 10" thick, with a tile or 12" - 60" of earth on top of it, and the entire house is on a slab-on-grade foundation, so there is no crawlspace or basement. The design calls for all of the ceilings to be "exposed" concrete. To maximize floor area, the design also calls for all the walls to have ether tile attached directly to the wall, or 2x2 or 2x4 furring strips to mount drywall to. At first glance, one might call this impossible to install a ducted system.

Note the continuous ventilation and "insulation". That's the only insulation specified for the house that we discovered has no radiant barrier, which makes it almost useless. No insulation will be put in the walls or ceilings, because they are all mostly below grade (thermal mass). The only I asked the builder to add insulation is on the concrete roof (with tile finish) over the Master Suite. Three inches of polyisocyanurate (approx. R-21) reduces the cooling load for the Master by 40%.

If the cavity of the wood roof structure was sealed tight and filled with high density (higher than R-4.2) insulation, the cooling loads for the Main Living Room area and Guest House would decrease by 20%. This wasn't enough to justify insulating and air sealing, so it was left uninsulated.

FINALLY - The Design

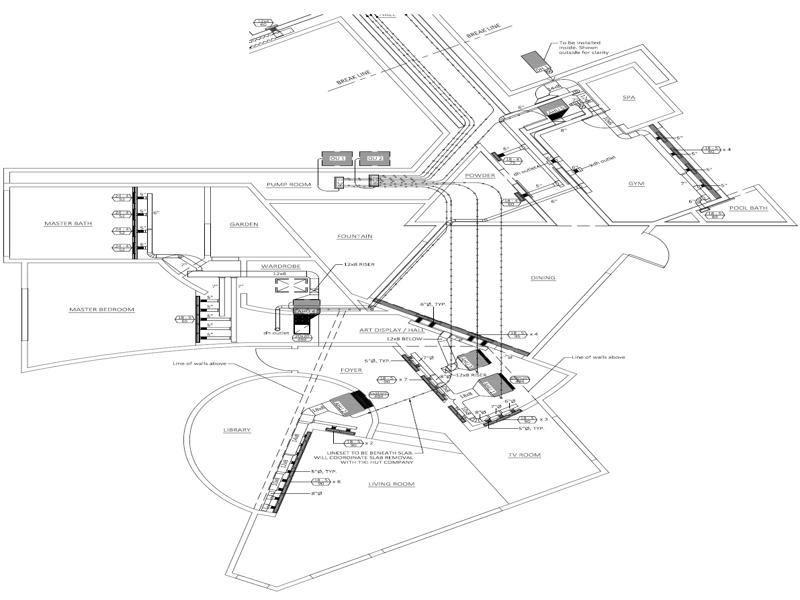

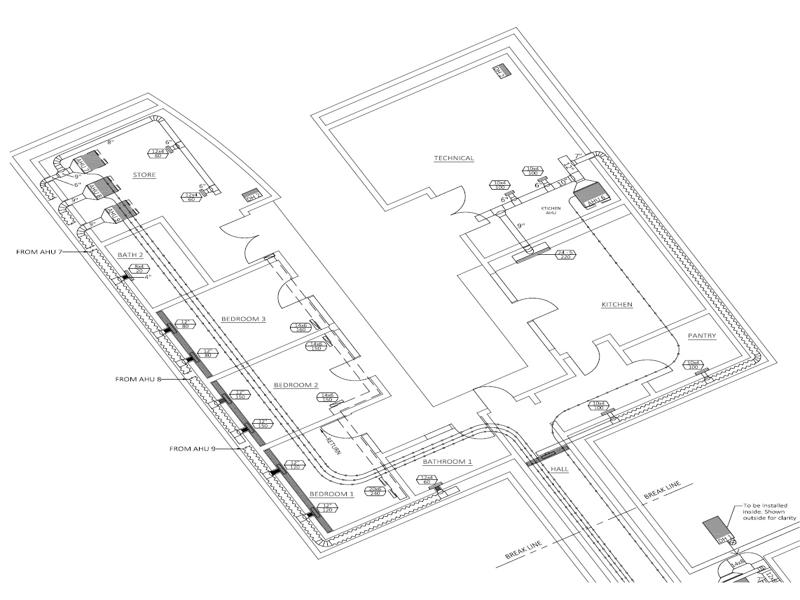

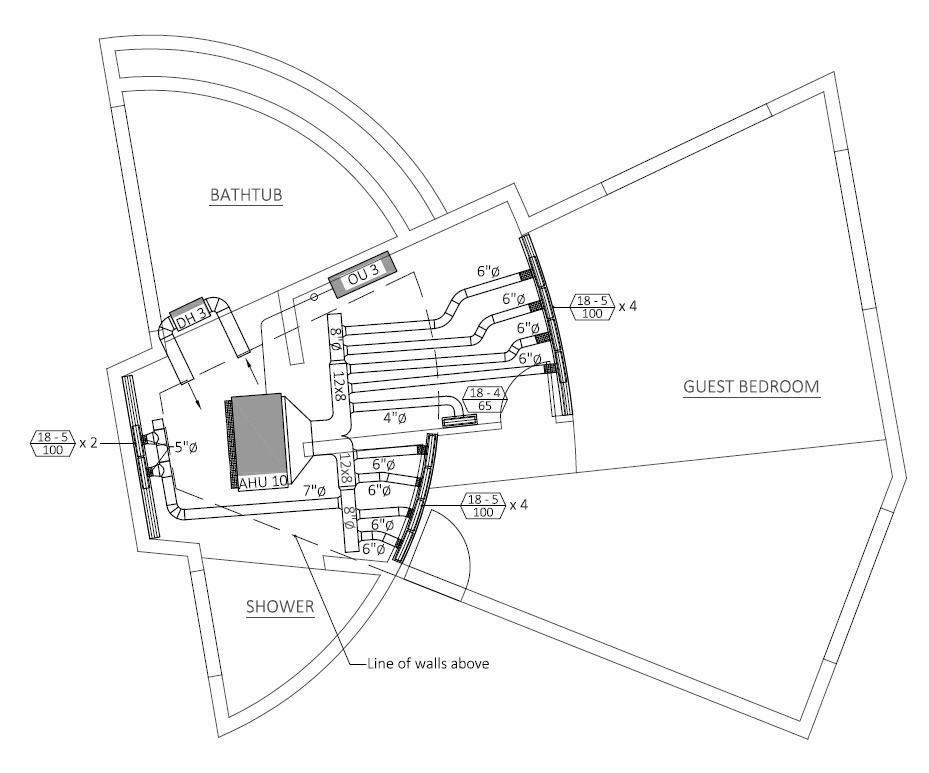

Given the climate, the architecture, the enclosure performance, and the owner's desire to not see or hear the systems, we determined that a ducted variable refrigerant flow (VRF) system, known as CITY MULTI, from Mitsubishi, was the most appropriate. Indoor and outdoor equipment is very quiet, and the air handlers are approximately 8" - 10" tall. This provided the flexibility with placement in the home, which we needed. The owner also wants the option to simultaneous heat and cool, if necessary, which this equipment can do. In fact, the efficiency of the equipment improves when in this mode. Although these systems will handle a portion of the humidity, we're installing standalone permanent dehumidifiers throughout to help handle the anticipated latent (moisture) loads from people, showers, cooking, infiltration, etc.

Here are the final plans:

That's it for now. Thanks for taking the time to visit and read what's happening at LG Squared. Lots of exciting things to come. In the meantime, here are a few "FUN" photos of The Bahamas that we took in between calculations ;-) It is one of the most amazing places on earth.

I would also like to take a second to thank my friend and mentor, David Butler, whom I consulted with on aspects of this and many other mechanical system design projects. He is one of the most patient, thorough, and knowledgeable people I know. I couldn't be where I am today without him.

...